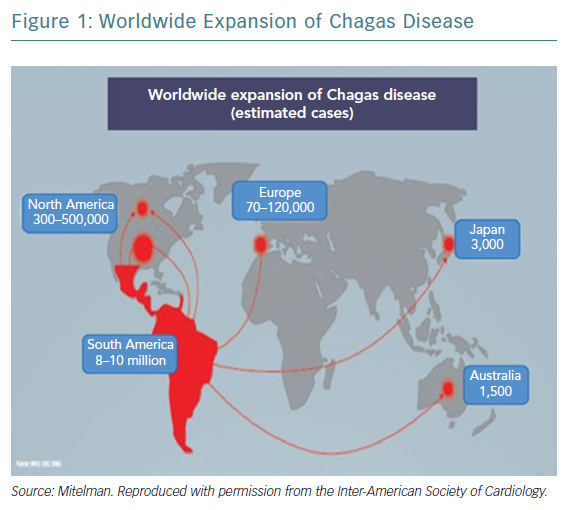

Chagas disease was initially described as an endemic health problem in a few countries in South America – mainly Argentina and Brazil – and one of the consequences of the disease, heart damage, made it an interesting issue for healthcare professionals, from epidemiologists to cardiologists.1 Chagas cardiomyopathy (ChCM) is now recognised as a cardiovascular disorder, diagnosed and treated not only in the original region, but also in Europe, North America and even in Asia (Figure 1). This is a result of increased migration around the world.2–4 It is estimated that Chagas disease affects 6–7 million people in Latin America and more than 300,000 people in the US.5,6 The natural history of the disease shows that after two to three decades up to 30% of infected individuals exhibit evidence of chronic cardiomyopathy and a proportion of these develop heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).7 Despite the high prevalence of Chagas disease, little is known about morbidity and mortality in patients with HFrEF caused by Chagas disease, compared with other aetiologies, especially in the modern era of HF therapies.8,9 Future trials should consider recruiting larger numbers of patients with ChCM to allow adequately powered subgroup analysis. We still treat patients with HF caused by ChCM empirically with therapies recommended by guidelines and this is another reason to specifically promote more research in ChCM.10 This article will analyse and discuss Chagas disease and HF, from epidemiology through to the latest treatment and prevention strategies.

The Expanding Epidemiology

Chagas disease is an important public health problem, with a frequency 140 times higher than HIV. Initiatives in the Americas have helped to achieve significant reductions in the number of acute cases of Chagas disease and the presence of domiciliary triatomine vectors in endemic areas. The estimated number of people infected with Trypanosoma cruzi worldwide dropped from 30 million in 1990 to 8–10 million in 2010, the annual incidence of infection decreased from 700,000 to 28,000 new cases over the same period and the burden of disease decreased from 2.8 million disability-adjusted life-years lost to <0.5 million years between 1990 and 2006.11 Approximately 108 million people are exposed to Chagas disease in 21 South American countries, with 8 million infected and 41,200 new cases per year. About 20–40% of infected people will develop cardiac damage.12–14 The prevalence of Chagas disease varies between countries, from 1.3% in Brazil to 20.0% in Bolivia. In the US, estimates claim that over 0.5 million immigrants are infected with T cruzi. The number of houses infested by triatomine vectors has been reduced as a result of campaigns and the work of teams throughout South America. Vectorial transmission has been stopped in Uruguay, Chile and Brazil, and in large areas of Argentina and Venezuela, achieving an average reduction in prevalence and incidence of 70%.

Chagas disease is an important cause of dilated cardiomyopathy in Latin America, where the disease is endemic.15,16 Chagas heart disease (ChHD) commonly presents with symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias, symptomatic bradyarrhythmias, sudden death, HF, embolic events, chest pain and high susceptibility to proarrhythmia.15 The clinical picture mimics that of coronary artery disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The prognosis is poor for patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias, HF, left ventricular aneurysm or global systolic dysfunction.16 Moreover, in an Argentinian survey, HF was the most frequent finding, leading clinicians to suspect Chagas disease.17

HF may occur in approximately 10% of subjects who have Chagas disease with cardiac involvement.18,19 A meta-analysis of 143 studies of HF from Latin America reported the incidence of HF in Chagas disease to be 137 per 100,000 people per year and annual mortality to be 1.12–7.18 per 100,000 people per year. Higher in-hospital mortality was also found in patients with Chagas disease, compared with a non-Chagas disease aetiology, representing 36% of the aetiology of HF.20 The estimated prevalence of Chagas disease within HF populations in Argentina is about 15%.21 However, data from different surveys reveal a Chagas disease prevalence of 4.0–6.0% in outpatient registries and 1.3–8.4% in decompensated HF settings in Argentina, and of 0.6–20.0% in Latin American registries.22–24 This discrepancy may be attributable to actual lower prevalence, underrepresentation of rural inhabitants in the surveys, low use of screening tests or because some cases of Chagas disease might represent a comorbidity. The Grupo de Estudio de la Sobrevida en la Insuficiencia Cardíaca en Argentina (GESICA) Registry has shown a prevalence of true ChCM of 6.4%.25 Patients with Chagas disease had a different clinical profile from, and were treated differently to, those without Chagas disease. Patients with ChCM were admitted more frequently for decompensated HF than other patients.26 It has been reported that long-term outcomes in patients with chronic systolic HF secondary to ChCM are poorer than those in patients with idiopathic and ischaemic aetiologies.27,28

Acute decompensated HF (ADHF) is a common clinical condition in ChCM. A study has shown that patients with ChCM had the highest proportion of hospital admissions for cardiogenic shock and arrhythmia, with lower systolic blood pressure and a higher proportion of right ventricular HF than other aetiologies.29 Outcomes were also influenced by aetiology, and ChCM had the lowest proportion of hospital discharge and the highest proportion of cardiac transplant when compared with other aetiologies, mainly in Latin American countries. So, the poorer prognosis of ChCM in comparison with other common causes of cardiomyopathy is also applicable to vulnerable ADHF, related to the severity of presentation and other issues, including socioeconomic factors.

Typically, the clinical profile of ChCM includes younger people, more often women, with lower prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and renal impairment, compared with non-ChCM patients. In contrast, health-related quality of life was worse and the prevalence of stroke and pacemaker implantation were higher in ChCM compared with non-ChCM aetiologies. Despite these differences, the rates of cardiovascular death, HF hospitalisation and all-cause mortality were higher in patients with Chagas disease than other non-ischaemic and ischaemic patients.9

Main Pathophysiologic Pathways

Chagas disease may be diagnosed in the infected patient in either acute or chronic clinical presentation. In some cases, the acute phase is light and can go undiagnosed by the patient and the medical team.

Acute Chagas disease is an immunological reaction typically characterised by diffuse lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. In this period the myocardium and the gastrointestinal system are severely infected by the parasite and show important tissue inflammation.30 Sometimes, acute myocarditis may be diagnosed with signs of cardiac dilatation and pericardial effusion. The most severe presentations may produce pancarditis and even vasculitis. In these cases, development of acute HF is frequent and the prognosis is usually poor because multiorgan involvement may occur.31,32

Development of HF linked to Chagas disease most commonly presents chronically. The typical dilated cardiomyopathy observed in most patients with chronic HF related to Chagas disease consists of chronic myocarditis producing fibrosis with particular invasion of His bundle branches, causing different types and grades of cardiac block and progressive dysfunction.33 The exact mechanism whereby parasitism causes tissue damage in the chronic phase is not clear and could be related to chronic immune reactions. The severity and extension of the inflammation and fibrosis depend on many factors, mainly the aggressiveness of the parasite, the immunologic reaction of the patient and the concomitant cardiovascular risk factors.34–36 Some patients with ChHD may also have digestive disturbances, often dysfunctions in the oesophagus and bowel as a result of inmunoinflammatory reactions in these organs, which ends in megaoesophagus, megacolon and/or megarectum.37

An Update on Diagnosis

In the acute phase of Chagas disease, the diagnosis might be suspected, taking account of the different transmission forms and patient history. Most patients are oligosymptomatic with non-specific symptoms of weakness, fever and malaise. Patients could present with the pathognomonic chagoma or unilateral eyelid swelling, which is often treated as viral conjunctivitis. In some cases – mainly in immunocompromised patients or in those who were infected with T cruzi through oral transmission – fulminant disease is present with acute myocarditis, pericardial effusion or meningoencephalitis.38–40

After the acute phase of infection, most patients develop the chronic form. This is defined by positive serology and slow progression or even absence, during a non-specific period of time, of physical signs or symptoms of cardiac electrogenic conduction abnormalities, myocardial contractile dysfunction, arrhythmias thromboembolism, colon, rectum or oesophagus abnormalities.41–46 ChCM is the most important clinical manifestation of Chagas disease, resulting in the majority of Chagas disease morbidity and mortality.39,41,47,48

ECG and Holter monitor

The ECG and Holter monitor may show tachycardia (out of proportion to fever), different degrees of atrioventricular (AV) block, QT prolongation, low voltage and repolarisation abnormalities in the acute phase of the disease.

Later in the disease progression, the ECG plays an important role in diagnosis and prognosis of ChCM. It could be normal, with slight abnormalities, premature ventricular beats, ventricular tachycardia, AF or flutter, complete AV block, anterior and inferior fibrosis, complete right bundle branch block alone or in combination with left anterior fascicular block, with or without different degrees of AV block.49

Radiology

X-ray is useful in assessment and follow-up of Chagas disease. Enlargement of all four cardiac chambers with or without signs of pulmonary congestion suggests ChCM.41 X-ray is also useful in the diagnosis of megacolon and megaoesophagus, which can be corroborated with endoscopy.

Parasitaemia

In the acute phase of Chagas disease, parasitaemia can be observed with a microscopic blood examination.49 Microhaematocrit is a widely used method of identifying congenital infection. The trypomastigotes present in the blood can be seen during the first 8–12 weeks and, after that, parasitaemia falls below detectable levels.50

Serology and C-reactive Protein

Indirect immunofluorescence, haemagglutination, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are commonly used in screening for Chagas disease.51–53 The WHO recommends diagnosing Chagas disease with two conventional laboratory tests and doing a third test in cases of discordance. C-reactive protein testing is the most sensitive test in acute infection or reactivation in patients with Chagas disease who are organ recipients or are otherwise immunocompromised.54–56

Echocardiography

Echocardiography may find segmental wall motion abnormalities, including akinesia, hypokinesia or dyskinesia with preserved septal contraction, left ventricular aneurysm (most common in apex), left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy involving both ventricles, and mural thrombus, mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

Assessment of myocardial strain through speckle tracking could help to detect myocardial damage in early periods of the disease, and some authors describe decreased global radial strain during the indeterminate stage, even in patients with a normal ECG and common echocardiogram.57–59 Left ventricular global dysfunction with low ejection fraction is one of the most important predictors of death in ChCM.57,59–61

Multigated Radionuclide Ventriculography

Multigated radionuclide ventriculography can be particularly helpful for the assessment of biventricular systolic function in patients with poor echocardiographic windows and a contraindication to cardiac MRI. It is an excellent method for providing LVF information in patients with Chagas disease.62,63 It can also provide us with quantification of right ventricular function – although this is less precise – and with echocardiographic analysis can be used to qualitatively assess ventricular dyssynchrony.64–66 These data could all be improved with myocardial perfusion assessment.67

PET

PET is not included as a routine investigation in Chagas disease but perfusion defects and areas of fibrosis can be detected with PET in early stages and they correlate with ventricular wall motility abnormalities in the absence of coronary artery lesions.68,69

The presence of chest pain – mostly non-typical angina pectoris – in patients with Chagas disease could be attributable to microvascular perfusion abnormalities.69,70

Cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI with or without gadolinium is useful to obtain more precise information about left ventricular ejection fraction and right ventricular ejection fraction, thrombus and fibrosis, giving us a good diagnostic and prognostic base.17,71–74

Cardiac Catheterisation

Although most patients with Chagas disease have normal epicardial coronary arteries, cardiac catheterisation is necessary to rule out epicardial coronary artery disease, which could coexist with Chagas disease, even in patients without angina pectoris or with non-characteristic chest pain.

Ventriculography allows the detection small aneurysms, which would not be detected with echocardiography, and left ventricular wall motion abnormalities. Right and left cardiac catheterisation is also indicated in patients with advanced HF to assess and more effectively tailor therapy and determine the feasibility of cardiac transplantation or the implant of a ventricular assist device.

In addition, continuous ambulatory pulmonary pressure monitoring could reduce decompensation episodes and reduce the number of hospitalisations in patients with HF.75–77

Drug Heart Failure Management: Similar or Different?

This update is specifically focused on the management of HF and not on the parasite-related therapeutic issues, nor on the other organs damaged by Chagas disease.

Treatment of cardiac dysfunction should be similar in populations with and without Chagas disease, as the haemodynamics and pathophysiology are similar. Treatment approaches have been based on evidence from other forms of HF and most clinical trials confirming a survival advantage did not include Chagas disease. So, information about treatment in patients with Chagas disease and HF derives from non-randomised studies or clinical trials of HF that included only small proportion of ChCM.78 Consequently, there are few therapies with strong recommendations and most of therapies are based on evidence from small trials and expert opinions.

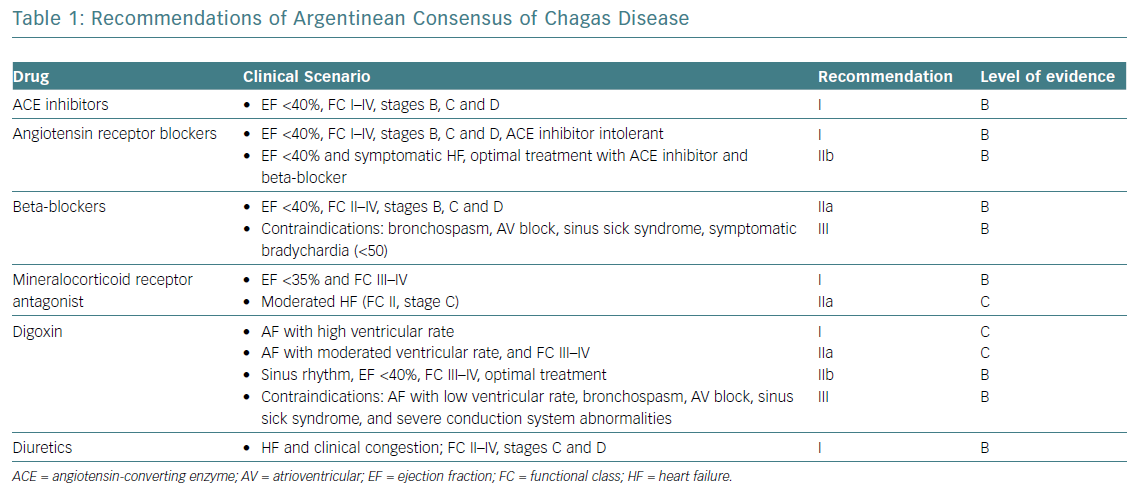

While specific pharmacological treatment of HF is common to other aetiologies, there are some significant features in the context of HF as a result of ChCM that should be considered. Table 1 shows the main recommendations from the Argentinian consensus document on Chagas disease.79

Routinely, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) represent the ideal combination in subjects with reduced ejection fraction, in the absence of any contraindications. In addition, digoxin, diuretics and anticoagulation are used as needed.80,81 Small trials in patients with cardiomyopathy have shown that these treatments can improve functional class, lower BNP and have a beneficial effect on neurohormones with a reduction in heart rate and decreased incidence of ventricular arrhythmias.3,82 Evidence for the role of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI) is lacking and only 7.6% of 2,552 Latin American patients with HFrEF randomised in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial and Aliskiren Trial of Minimizing OutcomeS in Patients With HEart Failure (ATMOSPHERE) had ChCM.83 Compared with other aetiologies, patients with ChCM less frequently received beta-blockers and digitalis, but a higher proportion were treated with amiodarone, MRA and anticoagulants, with no differences in the use of ACEI.

Although several clinical trials have demonstrated the utility of adrenergic blockers in dilated cardiomyopathy different from Chagas disease in terms of reducing mortality and the number of hospitalisations, in ChCM, the presence of significant bradycardia and autonomic nervous system disorders with central and peripheral dysautonomia lead to greater precautions for routine use. The most used drug in this condition is carvedilol. Three trials evaluating carvedilol in ChCM were identified, with a total of 108 participants.84 A lower proportion of all-cause mortality was found in the carvedilol groups compared with the placebo groups (RR 0.69; 95% CI [0.12–3.88]), with no difference in hospital readmissions. However, the authors found that the available evidence was low quality and there were no conclusive data to support or reject the use of carvedilol.

Diuretics should be used at the lowest possible dosage to obtain a negative balance, thus avoiding electrolyte and metabolic disorders caused by high dosages. Furosemide has the strongest diuretic effect and electrolytes should be checked frequently because excessive depletion can generate malignant arrhythmia.

Patients with severe HF as a result of heart disease not related to Chagas disease have shown improvement in quality of life and fewer hospitalisations when treated with digoxin, compared with placebo. However, ChCM has been associated with changes in automaticity and conduction related to malignant ventricular arrhythmia, and dysautonomia favours the appearance of bradycardic rhythms. Consequently, as digoxin can aggravate these disorders of rhythm and conduction, it has a restricted use in Chagas disease. Low-dose amiodarone has been associated with reduced HF mortality and sudden death in an Argentinian study that included patients with ChCM. A such, amiodarone can be safely used in the presence of arrhythmias. Anticoagulation in ChCM shares its common indication with other aetiologies, including permanent or paroxysmal episodes of AF, a previous thromboembolic event, the presence of a cardiac thrombus and apical aneurysms. A subanalysis of the Systolic Heart failure treatment with the If inhibitor ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) reported that ivabradine was effective in reducing heart rate in ChCM and improving functional class, suggesting that ivabradine may have a favourable benefit-risk profile in this population.85 Specific drugs to eliminate the parasite or its reactions and non-pharmacological or invasive therapies are explained in the following section.

Specific Antitrypanosomal Therapy

Treatment for Chagas disease is mainly non-invasive in the early stages, when nifurtimox or benznidazole are used. More invasive procedures could be applied in advanced stages of the pathology, for example, where there is pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, arrhythmia and HF.

Benznidazole is a nitroimidazole with antiparasitic effects. The side-effects include rash, numbness, fever, muscle pain, anorexia and weight loss, nausea, vomiting and insomnia, plus a rare but important symptom, bone marrow suppression, which can lead to low blood cell levels.

Nifurtimox forms a nitro-anion radical metabolite that reacts with parasite nucleic acids causing significant DNA breakdown. It is used as a second specific treatment option in early Chagas disease because it has more serious side-effects than benznidazole, including anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, amnesia, rash, depression, anxiety, confusion, fever, sore throat, chills, seizures, impotence, tremors, muscle weakness and numbness.

Invasive Treatment of Gastrointestinal Chagas Disease

Invasive procedures to treat megacolon and megaoesophagus may be necessary. Megacolon can be treated with the Duhamel procedure or a modified version of the procedure, introduced by Haddad.86–88 Laparoscopic procedures could also be applied. Megaoesophagus can be treated with wide oesophago-cardiomyectomy on the anterior oesophagogastric junction, combined with an antireflux valvuloplasty procedure or oesophagogastroplasty through the oesophageal bed.89 These procedures could be extremely useful when advanced stages of HF are present and it is necessary to offer more invasive procedures.

Invasive Treatment of Cardiovascular Chagas Disease

Cardiac manifestations of Chagas disease may also need invasive surgical procedures to preserve the patient’s life or improve their functional class. Clinical management of patients with chronic Chagas disease requires proper clinical risk stratification and the identification of patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). Recognising high-risk patients who require specific therapies – especially invasive procedures such as the implantation of pacemakers, automatic ICDs, ablative procedures and even cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) – is a major challenge in clinical practice.90

Pacemakers

Electrophysiological abnormalities of sinus node, AV node and His-Purkinje conduction can be detected in about one-third of patients with Chagas disease and pacemakers have shown utility in patients with this manifestation, but in some places this is still an unmet need.91–93 AV block and symptomatic sinus sick syndrome are the main indications for pacemaker implantation in these patients, preferably electrode implantation in the mid-septal of the right ventricle to the apical site.94

Automatic ICDs

Malignant ventricular arrhythmia and SCD are more frequent in patients with Chagas disease.91,95,96 Automatic ICDs may be used in the treatment of severe arrhythmias with high risk of SCD.97 Primary or secondary prevention should be a routine indication for patients with Chagas disease with malignant arrhythmias.98 The combination of ablation procedures, amiodarone and/or beta-blockers might be considered in special cases to reduce the number of automatic ICD therapies, as in other types of cardiomyopathy.99

Ablation Therapy

Ablation ventricular tachycardia therapy should be considered after oral medication failure.100 CRT could be used in the treatment of patients with severe HF and left bundle branch block but there is scarce evidence to support resynchronisation therapy for patients with ChCM and right bundle branch block or its combination with left anterior fascicular block, where experience is not conclusive.101,102

Ambulatory Pulmonary Pressure Monitoring

Other less invasive procedures such as ambulatory pulmonary pressure monitoring, which are useful in patients with HF, need to be tested in patients with Chagas disease HF and could probably prevent recurrent episodes of decompensation.75,77

Heart Transplant

Heart transplantation and left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) have an important place in the treatment of irreversible HF in patients with Chagas disease.

Chagas disease was initially considered a contraindication for transplantat because of the possible reactivation after transplantation and immunosuppression, but advances in immunosuppression programmes since the 1990s mean that there is now a similar survival and quality of life in HF patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy.103 Selection criteria are similar to those for general heart transplant, including pulmonary artery pressures that could be elevated in some cases as a result of chronic left ventricular failure or undiagnosed pulmonary microembolism. However, the clinician also needs to consider the presence of megaoesophagus or megacolon, which could constitute a contraindication because of the possibility of complications (perforation) with the use of antiproliferative therapy such as mycophenolic acid derivatives or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors. The administration of prophylactic antitrypanosomal therapy is not recommended because of the higher risk of malignant neoplasms after transplant in patients who received reactivation prophylactic antitrypanosomal therapy.104 The lowest immunosuppression regimen, high suspicion of possible reactivation and early detection and introduction of medical treatment with benznidazole offer a secure treatment of Chagas disease reactivation after transplant. Lifelong T cruzi monitoring is required, mainly during increased immunosuppression therapy for transplant organ rejection.105,106

Circulatory Assist Devices

Different devices for cardiac assist could be used in patients with end-stage HF as a result of Chagas disease. These could be applied as a bridge to transplant, a bridge to recovery during the acute period or as a bridge to decision, or even as destination therapy depending on the general state of the patient and meticulous clinical evaluation of the possibility of survival and better quality of life.107–110

As in the transplant population, previous evaluation of the pulmonary pressures plus poor right ventricular function could be a contraindication for LVAD alone.

Global Action on Chagas Disease

ChHD is a preventable non-communicable disease (NCD) that mainly affects the poorest and most vulnerable populations of South America. Driven by poverty, poor access to health services and other health system weaknesses, the majority of people with this condition live in low- and middle-income countries.

The need for concerted global action to control NCDs is a high priority on the global health agenda. This is evident in the UN political declarations on the prevention and control of NCDs – the 25×25 target aims for a 25% reduction in premature mortality from NCDs by 2025 – the WHO Global NCD Action Plan, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.111,112

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of premature mortality worldwide and with more than 80% of deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries, leading the World Heart Federation (WHF) to launch its Roadmap Initiative in 2014 to guide and support those seeking to improve CVD control.

The WHF Roadmaps are global implementation strategies designed to help governments, employers, non-governmental organisations, health activists, academic and research institutions, healthcare providers and people affected by CVD, take action to better prevent and control CVD.113,114 The Roadmaps synthesise existing evidence on the efficacy, feasibility and cost-effectiveness of various strategies. They also identify potential barriers (roadblocks) to implementation and propose solutions to bypass them. The WHF and Inter-American Society of Cardiology Roadmap for reducing morbidity and mortality through improved prevention and control of ChHD complements existing Roadmaps on tobacco control, hypertension, secondary prevention of CVD, rheumatic heart disease, cholesterol, AF, diabetes and HF. The ChHD Roadmap is a resource to raise the profile of ChHD and provides a framework to guide and support the strengthening of national, regional and global ChHD control efforts. The process also requires a range of local expertise, including knowledge of medicine, cardiology, cultural and social contexts, prevention, health promotion, health systems, economics and government priorities.

Conclusion

Chagas disease – originally a South American endemic health problem – is expanding worldwide as a result of people migrating. The pathology of Chagas disease is based in an inmunoinflammatory reaction producing fibrosis and remodelling, mainly in the myocardium. In many cases these mechanisms result in a dilated cardiomyopathy with HF and reduced ejection fraction, frequent cardiac arrhythmias and different types of heart block. The diagnosis and treatment of HF as a result of Chagas disease include the usual steps for other aetiologies, plus the need for laboratory techniques for parasite-related issues. International scientific organisations are concerned about this health problem and about delivering recommendations for prevention and early diagnosis.