Coronary Artery Spasm and Adventitial Inflammation

Coronary artery spasm plays an important role in the pathogenesis of a wide range of ischaemic heart disease, not only in variant angina, but also in other forms of angina pectoris and myocardial infarction.1,2 Recent studies have demonstrated that coronary spasm is also as frequently noted in European people as in Asian people.3

We have previously demonstrated that activation of Rho kinase, a molecular switch for vascular smooth muscle cell contraction, is a central mechanism of coronary spasm in animals and humans.1,4,5 In addition, we demonstrated that coronary spasm can be induced without endothelial dysfunction in a porcine model with chronic adventitial application of interleukin-1 beta through Rho kinase activation.6 In these studies, we demonstrated that vascular smooth muscle cell hypercontraction induced by adventitial inflammation through Rho kinase activation, rather than endothelial dysfunction, plays a major role in the pathogenesis of coronary spasm.1,4,5

We also recently demonstrated that optical coherence tomography (OCT) enables us to precisely observe the adventitial vasa vasorum (VV) area, and that adventitial inflammatory changes, including VV formation, play important roles in the pathogenesis of coronary spasm in pigs and humans.7–9

Perivascular Adipose Tissue

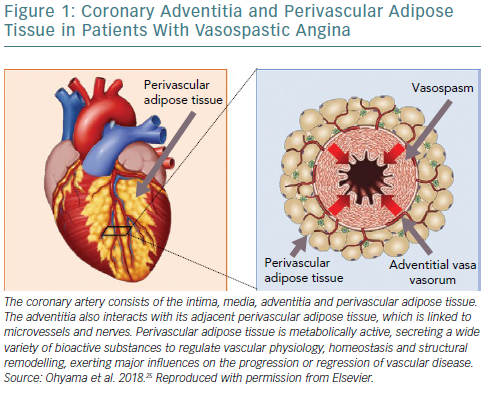

The coronary artery consists of the intima, media, adventitia and perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT; Figure 1). The adventitia completely surrounds the media and thus mediates communication with medial vascular smooth muscle cells.1,10 The adventitia also interacts with its adjacent PVAT, which is linked to microvessels and nerves, to regulate vascular physiology, homeostasis and structural remodelling, exerting major influences on the progression or regression of vascular disease.10

Ectopic adipose tissue, defined as the deposition of fat in non-classical locations including the heart and blood vessels, may contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease by exerting a local toxic effect on adjacent vasculature.11–13

One such ectopic adipose tissue is PVAT, which is directly adhered to blood vessels. PVAT, similarly to other adipose tissues, is metabolically active, secreting a wide variety of bioactive substances.14

Indeed, Owen et al. also reported that inflamed PVAT exerts augmented contractile effects through Rho-dependent signalling in pigs ex vivo.15

Thus, much attention has been focused on identifying the inflammation and metabolic activity of PVAT in experimental animals and humans.15–18 Indeed, recent advances in translational research using non-invasive imaging modalities, including 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET and cardiac CT, have enabled us to visualise perivascular inflammation.

In this brief review, we provide an overview of the recent progress in imaging for PVAT inflammation, particularly in the field of coronary artery spasm.

Cardiac CT for Evaluation of Perivascular Adipose Tissue

Validation Studies

Although it has been considered to be technically difficult to directly detect PVAT or vascular inflammation on cardiac CT, inflammatory changes of PVAT have been emerging as a surrogate marker to detect the changes.16 Antonopoulos et al. reported that human vessels exert paracrine effects on the surrounding PVAT, affecting local intracellular lipid accumulation in preadipocytes, which can be monitored using a CT imaging approach.16 They examined human adipose tissue explants and their CT images from patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and developed a new imaging metric, termed as the CT fat attenuation index (FAI), that effectively describes adipocyte lipid content and size. The FAI has excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting tissue inflammation, as assessed by tissue uptake of 18F-FDG PET. The FAI gradient around human coronary arteries effectively detected early subclinical coronary artery disease in vivo, as well as dynamic changes of PVAT. Indeed, we also demonstrated that adipocyte size significantly differed between the spastic site after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation and the control site in our experimental study.19

Clinical Relevance

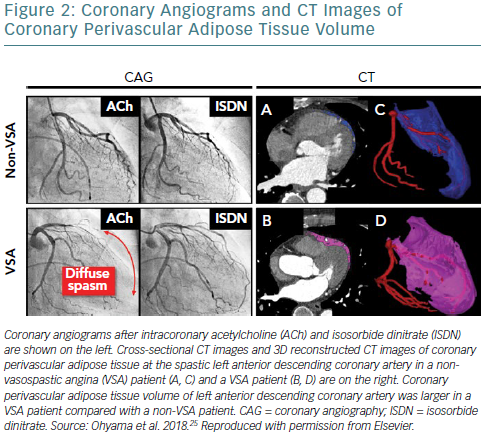

There is growing evidence suggesting that epicardial adipose tissue volume measured by cardiac CT is related to the extent of coronary plaque burden,20 and is also significantly associated with cardiovascular events.21 We recently demonstrated for the first time that coronary PVAT volume is increased at the spastic coronary segment of vasospastic angina (VSA) patients, suggesting the involvement of coronary PVAT in the pathogenesis of coronary spasm.22 Subsequently, Ito et al. reported that increased epicardial adipose tissue volume was associated with ergonovine-induced epicardial coronary artery spasm.23

However, our previous findings indicated that local adventitial inflammation including PVAT, but not systemic inflammation, plays important roles in the pathogenesis of coronary spasm.1,7,9 We thus suggested that increased PVAT volume of the spastic coronary segment could result in enhanced overall epicardial adipose tissue volume in the study by Ito et al.24 In addition, in our prospective clinical study, we confirmed that coronary PVAT volume was significantly increased at the spastic left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery in VSA patients compared with non-VSA patients, although there were no significant differences in bodyweight, body mass index or percentage of body fat between the two groups (Figure 2).25 This finding indicates that coronary PVAT per se, but not bodyweight or other adipose tissue, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of VSA. Importantly, there was a significant positive correlation between the extent of the coronary PVAT volume index and that of coronary vasoconstricting responses to acetylcholine in VSA patients.23 Interestingly, the Cardiovascular Risk Prediction using Computed Tomography (CRIPT-CT) study recently showed that high perivascular FAI values are an indicator of increased cardiac mortality in patients with atherosclerosis by providing a quantitative measure of coronary inflammation.26

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET for Perivascular Adipose Tissue Inflammation

Validation Studies

18F-FDG PET has been clinically used to detect inflammation, as it reflects the metabolic activity of glucose, which is known to be enhanced in inflamed tissue.27 Indeed, 18F-FDG PET can non-invasively image the metabolic activity in perivascular, visceral and subcutaneous fat tissues, serving as a surrogate marker for fat tissue inflammation.28,29 Indeed, Tarkia et al. demonstrated that, in early coronary atherosclerotic lesions, plaque inflammation with clearly increased uptake of 18F-FDG can be detected in a pig model of diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia.18

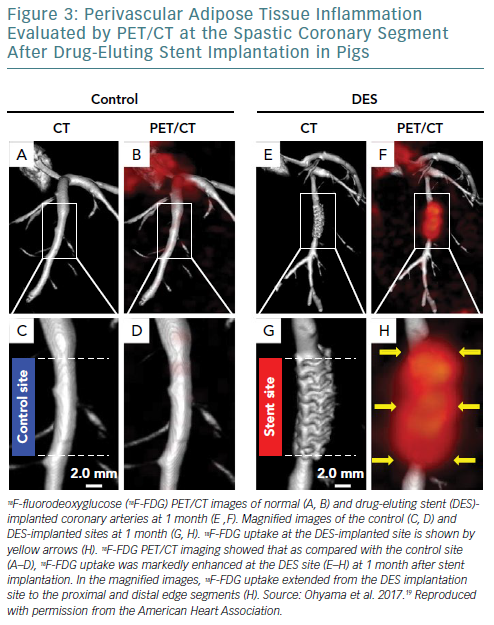

We also recently demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET/CT is useful for assessment of coronary PVAT inflammation in pigs in vivo in the pathogenesis of coronary spasm after DES implantation (Figure 3).19 In that experimental study, an everolimus-eluting stent (EES) was randomly implanted in pigs into the LAD or the left circumflex coronary artery, while a non-stented coronary artery was used as a control. At 1 month after EES implantation, coronary vasoconstricting responses to intracoronary serotonin were examined by coronary angiography in pigs in vivo, followed by in vivo and ex vivo 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Coronary vasoconstricting responses to serotonin were significantly enhanced at the EES edges compared with the control site. Notably, in vivo and ex vivo 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging and autoradiography showed enhanced 18F-FDG uptake and its accumulation in PVAT at the EES edges compared with the control site, respectively. Furthermore, histological and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that inflammatory changes of coronary PVAT were significantly enhanced at the EES edges compared with the control site. Importantly, Rho kinase expressions and Rho kinase activity at the EES edges were significantly enhanced compared with the control site in pigs. This basic research indicates that inflammatory changes of coronary PVAT are associated with DES-induced coronary hyperconstricting responses in pigs in vivo, and that 18F-FDG PET imaging is useful for assessment of coronary PVAT inflammation.

Clinical Relevance

Several studies demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET is clinically able to detect PVAT inflammation in patients with coronary atherosclerosis.16,22,23 Mazurek et al. reported that inflammatory activity of PVAT assessed by 18F-FDG PET was greater in patients with stable coronary artery disease than in non-coronary artery disease controls, and was independently associated with the extent of coronary stenosis.17 Hong et al. also reported that pericardial adipose tissue was significantly associated with vascular inflammation and various cardiometabolic risk profiles.30

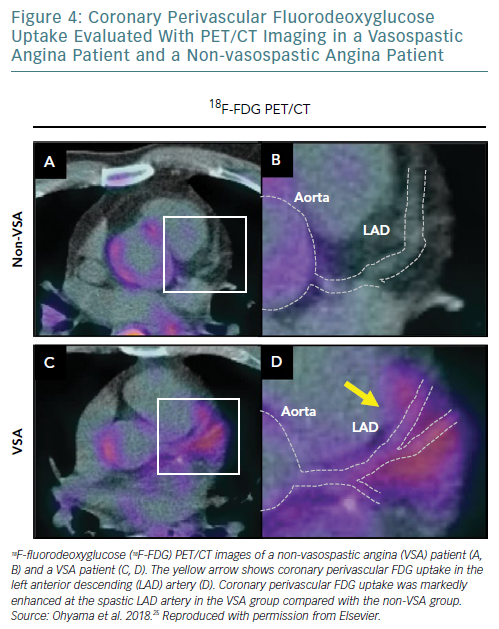

Furthermore, based on our experimental validation study, we also recently demonstrated with ECG-gated 18F-FDG PET/CT that coronary artery spasm was associated with perivascular inflammation in patients with VSA (Figure 4).25 In that clinical study, after excluding patients with ≥75% organic stenosis in the LAD artery, we prospectively examined 27 consecutive VSA patients with acetylcholine-induced diffuse spasm in the LAD artery and 13 individuals with suspected angina, but without organic coronary lesions or coronary spasm. ECG-gated 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed to measure coronary perivascular FDG uptake. OCT was also performed to evaluate the VV of the LAD artery. 18F-FDG PET/CT images showed that coronary perivascular FDG uptake was significantly increased at the spastic LAD artery in the VSA group compared with the non-VSA group. OCT examination showed that adventitial VV area density per a cross-sectional OCT image at the spastic LAD artery was markedly greater in the VSA group than in the non-VSA group. Importantly, after 23 months’ follow up with medical treatment, coronary perivascular FDG uptake was significantly decreased in the VSA patients. Rho kinase activity in circulating leukocytes increased in the VSA patients, and substantially decreased after medical treatment. Thus, that clinical study demonstrated that coronary spasm is associated with coronary adventitial and PVAT inflammation, where 18F-FDG PET/CT may be useful for disease activity assessment.23

Although we and others previously demonstrated that atherosclerotic changes, such as focal VV formation, may be involved in the focal spasm compared with the diffuse spasm in VSA patients,31,32 further detailed mechanisms of the type and location of coronary spasm remain to be elucidated in future studies.

Future Perspectives

Other perivascular components, such as sympathetic nerve fibres (SNFs) and lymphatic vessels, begin to attract much attention as crucial players regarding perivascular inflammation. We recently demonstrated that after DES implantation in pigs in vivo, adventitial SNFs can be enhanced, and are associated with adventitial VV growth. Catheter-based renal denervation also significantly upregulates the expression of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor-binding sites in the nucleus tractus solitarius, and attenuates adventitial VV enhancement associated with a decrease in SNF.33

We also recently demonstrated that cardiac lymphatic vessels (LVs) play important roles in the regulation of coronary vasomotion after DES implantation in pigs in vivo.34 In that study, after ligation of the proximal LV close to the left main coronary artery, coronary vasoconstricting responses at DES edges were significantly enhanced in the ligation group compared with the sham group. Importantly, LVs have drainage effects of inflammatory substances from PVAT, and thus may be one of the most crucial regulators for PVAT inflammation.35 Thus, the roles of these perivascular components (e.g. SNF and LV) also remain to be fully elucidated in future studies.

Antonopoulos et al. reported that interactions between the vascular wall and PVAT play an important role for adiponectin in the regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase function in patients with atherosclerosis.36,37 They introduced the novel concept that increased oxidative stress in the vessel wall leads to the release of peroxidation products (i.e. 4-hydroxynonenal) that upregulate adiponectin gene expression in PVAT via a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent mechanism, which also suggests the importance of inside-out signalling (i.e. from the vessel to surrounding PVAT). Further studies are required to elucidate the roles of inside-out signalling in cardiovascular disease in future studies.

Conclusion

Recent advances in non-invasive imaging for PVAT inflammation have begun to elucidate the roles of PVAT in the pathogenesis of coronary artery spasm. These imaging approaches for coronary perivascular components will enable us to elucidate the important roles of the coronary adventitia and the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease.