In the last months of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, a novel disease appeared, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a very contagious virus, which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The clinical manifestations of this virus in humans vary widely from asymptomatic to severe, with diverse symptomatology and even death. The substantial transmission from asymptomatic people has facilitated the widespread transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and contributed to its pandemic potential, thereby hampering public health initiatives to identify and isolate infected people and the estimation of overall infectivity in the general population. Thus, containment measures aimed solely at isolating symptomatic individuals are inadequate. Specifically, potentially exposed people during the pre-symptomatic contagious period need to be identified and isolated for fast interruption of the transmission process. COVID-19 is associated with cardiac complications that can progress from mild to life-threatening. The aim of this review is to analyse the present knowledge of COVID-19 regarding arrhythmia risk and its treatment.

Basic Virology Data

The Coronaviridae constitute a family of enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense, RNA viruses with a characteristic crown, or corona, of electron density seen on transmission electron microscopy. The lifecycle of SARS-CoV-2 is presumed to be similar to SARS-CoV-1 and other coronaviruses.1 SARS-CoV-2 spreads primarily through small respiratory droplets from infected individuals that can travel approximately 1–2 m. Live virus has also been isolated and cultured from faecal specimens, raising the possibility of orofaecal transmission, although clinical evidence for this mode of transmission is lacking.2 The virus can exist in nature on surfaces from hours to several days.3 Several aspects of SARS-CoV-2 remain unknown and are under intensive investigation globally.

SARS-CoV-2 is known to bind to cells via the membrane-bound glycoprotein angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).1 Thus, the role of the ACE2 molecule has been the subject of attention, given that it has a very broad expression in humans (e.g. type II pneumocytes, myocardium and endothelium). At this time, it is unclear if the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) influences receptor expression, thereby affecting the propensity or severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, in a case-population study from seven Spanish hospitals, analysing data from 1,139 cases (aged 18 years or older with a PCR-confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 requiring admission) and 11,390 population controls, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors did not increase the risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital, including fatal cases and those admitted to intensive care units, suggesting that they and should not be discontinued to prevent a severe case of COVID-19.4 Major societies have recommended continuation of ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy in patients with a previous indication for these drugs.5,6

Symptomatology

The largest (n=72,314) published registry of COVID-19 patients reported high-level details for putative (47%) and confirmed (63%) COVID-19 cases.7 In this population, predominantly identified by the presence of symptoms (approximately 99%), age plays a major role in the infection rate and also in the prognosis and <2% of cases occurred in individuals <19 years of age. Of confirmed cases, most (81%) were mild, 14% were severe with significant pulmonary infiltrates or signs of respiratory compromise, and 5% were critical with respiratory failure (e.g. mechanical ventilation), shock or multiorgan system failure. The estimated case fatality rate was <1% in patients <50 years; 1.3% in those aged 50–59 years; 3.6% for 60–69 years, 8% for 70–79 years, and 14.8% in those aged ≥80 years.7

The most common symptoms are fever in up to 90%, followed by cough, fatigue, sputum production and shortness of breath.8 Less common symptoms include headache, myalgia, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, but anosmia and dysgeusia have also been described. Blood abnormalities include lymphopenia, elevations in D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, transaminases and C-reactive protein (CRP), and interleukin (IL)-6, ferritin and others.8–12

Development of acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS), along with acute cardiac injury, have been described as independent predictors of death.13 Importantly, hypoxaemic respiratory failure is the leading cause of death in COVID-19, contributing to 60% of deaths.14

Cardiac Involvement

The reported rate of cardiac injury varies between studies, from 7% to 28% of hospitalised patients, and is related to worse outcomes, including intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death.9,10,12–15 Importantly, early cardiac injury has been reported, even in the absence of respiratory symptoms and signs of interstitial pneumonia.16 The mortality rate for those hospitalised with subsequent evidence of cardiac injury was significantly higher than for those without cardiac injury (51.2% versus 4.5%, respectively, p<0.001) and hence, along with ARDS, it is an independent predictor of death.13

The presence of previous cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes or arterial hypertension) or cardiac disease (previous MI or heart failure), as well as the presence of other clinically relevant comorbidities (e.g. older age, renal failure or prior lung disease), seems to worsen the prognosis of infected people.10–12,15 Furthermore, the infection is also associated with de novo cardiac complications (approximately 8–12% of myocardial lesions and 7–16% of myocarditis and arrhythmias).17

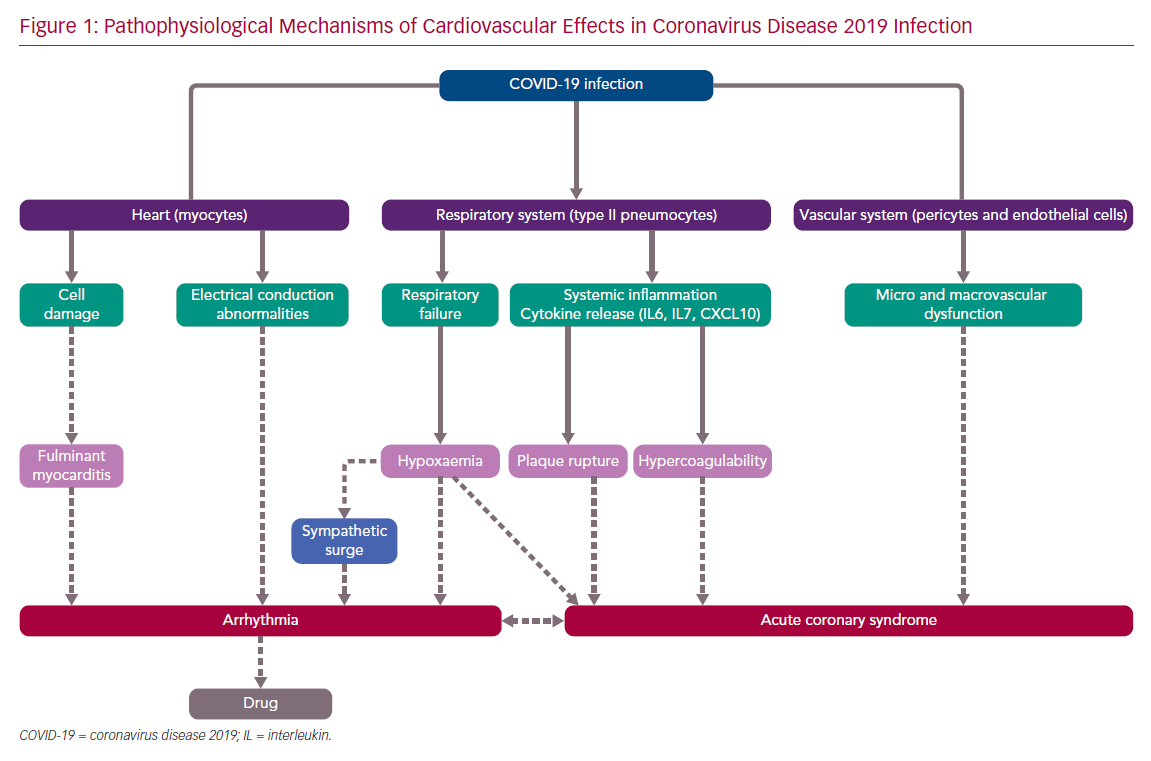

SARS-CoV-2 infection can affect the cardiac structures via various mechanisms of injury (Figure 1), such as by direct damage to the myocytes and the vascular cells, and also indirectly by cytokine expression after systemic inflammation. The infection provokes a disarray of the coagulation and fibrinolytic system, with a clinical picture consistent with disseminated intravascular thrombosis. Therefore, empiric anticoagulation is being used in some centres. In addition, an oxygen supply/demand mismatch or severe hypoxia caused by respiratory failure may modulate the cardiac affects, which may include myocarditis, acute coronary syndrome (ACS; type 2 MI) and arrhythmia, which might lead to acute or chronic heart failure.12–19

Furthermore, the arrhythmia occurrence (e.g. AF with fast ventricular response) may facilitate ischaemia, which can also cause arrhythmias (e.g. VF). In addition, some cardiotoxic drugs or drugs affecting the electrical properties of the heart may facilitate proarrhythmia (e.g. drugs prolonging the QT interval may facilitate torsades de pointes tachycardia). Thus, patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection may have heart rhythm disturbances due to a variety of mechanisms, which are interrelated and inter-facilitated. The role of stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy in COVID-19 patients is not known. However, several of the proposed mechanisms of COVID-19-related cardiac injury are also thought to be implicated in the pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy (particularly microvascular dysfunction, cytokine storm and sympathetic surge), and one typical takotsubo syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection has already been reported.20

Arrhythmia

The clinical manifestations (i.e. palpitations, syncope etc.) of bradyarrhythmias or tachyarrhythmias in COVID-19 do not differ from the usual presentation. No specific ECG patterns have been described in SARS-CoV-2-infected people. Thus, ECG diagnostic criteria are the same for infected and for the general population.

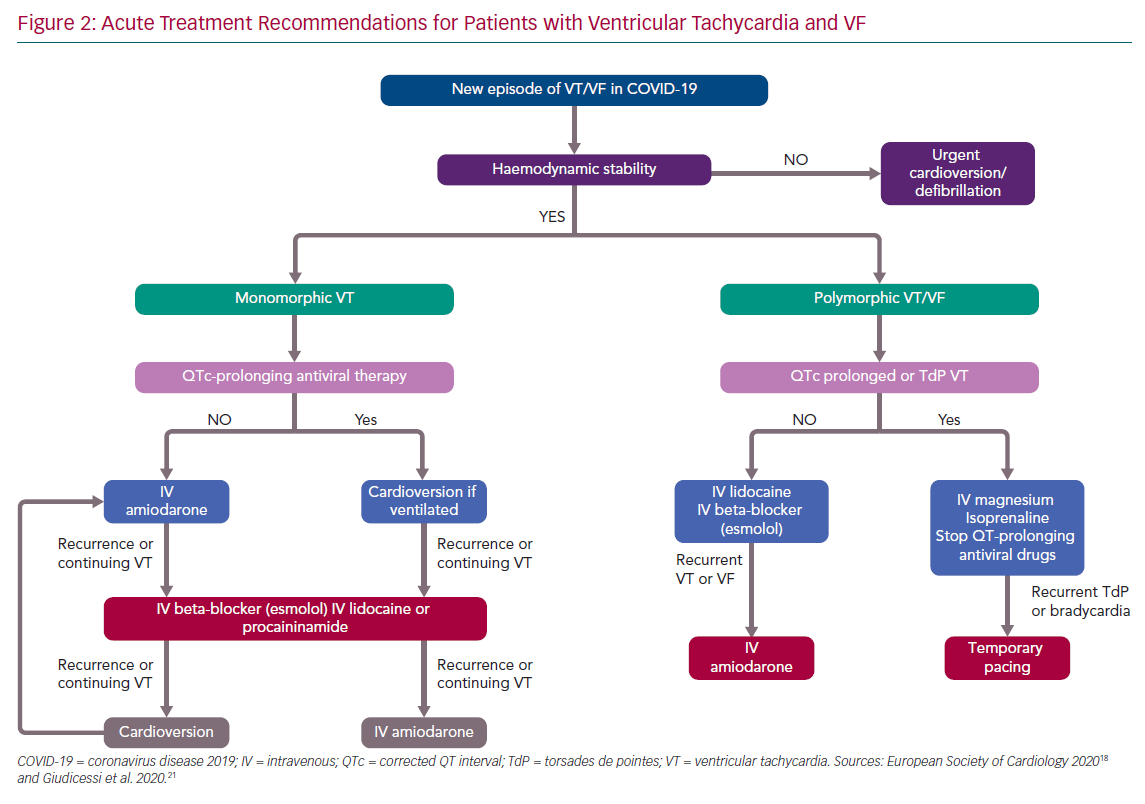

Surprisingly, there is limited literature regarding arrhythmias in COVID-19. The true incidence and type of arrhythmia is unknown. A large observational multicentre study from China of data on 1,099 patients did not report any arrhythmia.8 In a case series of 138 hospitalised patients with COVID-19, 16.7% (n=23) developed non-specified arrhythmias during their hospitalisation; higher rates were noted in patients admitted to the ICU (44.4%, n=16).10 A case series of 187 hospitalised patients provided insight into specific arrhythmias, reporting sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) or VF in 5.9% (n=11) of the patients.9 Interestingly, the incidence of these arrhythmias was 1.5% and 17.3% in those patients without and with troponin elevation (p<0.001),9 suggesting that new-onset malignant ventricular arrhythmias could be a marker of acute myocardial injury, and therefore a more aggressive immunosuppressive and antiviral treatment is needed. Figure 2 shows recommendations for acute therapy for patients with VT/VF.18,21 After recovery from COVID-19, the need for secondary prophylactic ICD, catheter ablation, or wearable defibrillator (in the case of suspected transient cardiomyopathy due to myocarditis) needs to be evaluated. There is currently no specific recommendation for acute myocarditis treatment.

Furthermore, there are no specific reports on COVID-19 in patients with channelopathies. There are, however, some special considerations. In patients with congenital long QT syndrome with SARS-CoV-2 infection, QT-prolonging antiviral drugs must be closely monitored and reconsidered if the corrected QT interval (QTc) is prolonged >500 ms or if it increases >60 ms from baseline.21 Electrolyte disturbances must be avoided and kalaemia should be kept at >4.5 mEq/l. To avoid fever-triggered ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with Brugada syndrome, fever must be intensively treated (mainly with paracetamol) and continuous ECG monitoring is recommended. Drug interactions with antivirals should also be strictly monitored in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic VT taking beta-blockers and flecainide. Catecholamines should be avoided if possible in these patients.18,22 Also, as part of the anti-arrhythmia treatment, all possible underlying reversible triggers (e.g. hypoxia, acidosis, electrolyte abnormalities and ischaemia) for arrhythmias should be eliminated.

The true incidence of new-onset AF in SARS-CoV-2 infection is unknown. Half of severely ill patients with cardiac involvement present with AF, given that it may be triggered by the infection alterations (e.g. fever, hypoxia and adrenergic tone).23 In a report from Italy, a retrospective chart review identified a history of AF in 24.5% of 355 COVID-19 patients who died (mean age 79.5 years).24

If inpatients present with AF or flutter with haemodynamic stability, a rate control strategy is reasonable, whereas cardioversion should be considered if haemodynamic instability occurs. Discontinuation of anti-arrhythmic drugs should be considered in patients with new-onset AF/flutter with haemodynamic stability under antiviral treatment, using rate control therapy with beta-blockers with/without digoxin.

Anticoagulation should be guided by CHA2DS2-VASC score. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are preferred over vitamin K antagonists in eligible patients (i.e. those without mechanical prosthetic heart valves, moderate to severe mitral stenosis or antiphospholipid syndrome) in order to avoid the need for regular determination of international normalised ratio but, considering possible drug–drug interactions, appropriate doses should be ensured.25,26 There is no specific information regarding the use of DOACs in COVID-19 patients. If necessary, apixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban (but not dabigatran) can be given in a crushed form. This is because dabigatran should always be given in capsule form in clinical use to avoid unintentionally increased bioavailability of dabigatran etexilate. However, if antiretroviral drugs are used, apixaban and rivaroxaban should be avoided because of potential interactions.18 Severely ill patients may be switched to parenteral anticoagulation, given that heparin does not present significant drug–drug interactions with COVID-19 treatment (except azithromycin, which should not be coadministered with unfractionated heparin). After recovery from COVID-19, the therapeutic choices of rate or rhythm control of AF/flutter should be re-evaluated, but long-term anticoagulation should be continued based on CHA2DS2-VASC score.18,22,25,26

Transient atrioventricular block has been rarely reported in COVID-19.27 A lower heart rate than expected in patients with fever has been observed in COVID-19 patients. In addition, some drugs used for COVID-19. (e.g. chloroquine and, less frequently, hydroxychloroquine) might increase the likelihood for AV block (sometimes after many weeks of treatment). Thus, patients must be informed about possible corresponding symptoms (i.e. dizziness or syncope). If persistent bradycardia occurs, all drugs that might aggravate this clinical problem should be stopped and heart rate-increasing drugs (e.g. isoprenaline or atropine), or temporary pacing must be considered. Implantation in patients with an indication for a permanent device should be delayed if possible to diminish the risk of nosocomial infection.

Although amiodarone has experimental antiviral properties that should be further analysed, anti-arrhythmic drugs should be used with caution to avoid proarrhythmia.28 However, in critically ill patients with haemodynamic instability caused by recurrent VT/VF, IV amiodarone is the anti-arrhythmic drug of choice, but its combination with other QT-prolonging drugs (e.g. hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin) should be avoided.18,22

Ventricular function and myocardial involvement should be assessed on echocardiography in patients with new severe ventricular arrhythmias. However, all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures should be restricted to those mandatory for immediate therapeutic management of critically ill patients, in order to preserve healthcare resources and minimise the risk of nosocomial infection.

Monitoring and follow-up of patients with implanted devices (e.g. pacemakers and ICDs) should be done remotely as much as possible. In this context, elective procedures should be postponed and urgent ones undertaken only after consideration of pharmacological alternatives and in designated catheterisation laboratory areas with appropriate personal protection equipment.

Other Treatments

Presently, there are no coronavirus-specific drugs available, and different approaches based on previous antiviral experience are used.29 The most widely applied inhibitor of viral genome replication agent against SARS-CoV-2 is remdesivir, which has in vitro activity against the virus.18,29,30 In addition, remdesivir has been reported to reduce the time to clinical improvement, but without statistically significant clinical benefits.31 Thus, the precise role of this drug (and several others) deserves further investigation.15

The antiviral properties (inhibition of membrane fusion) of chloroquine were previously observed in HIV and other viruses.32,33 Similarly, hydroxychloroquine is being widely used with an emergency authorisation.18,19,34–36 However, data are needed to prove efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in humans. In an observational study, among patients hospitalised in metropolitan New York with COVID-19, treatment with hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin or both, compared with neither treatment, was not significantly associated with differences in in-hospital mortality.35 However, in a US multi-centre retrospective observational study analysing data from 2,541 patients, treatment with hydroxychloroquine alone and in combination with azithromycin was associated with reduction in COVID-19-associated mortality when controlling for COVID-19 risk factors.36 It should be noted that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine prolong the QT interval and may induce life-threatening arrhythmias.37,38 Thus, caution should be used in starting these agents in patients with QTc >450 ms. Concomitant use of other QT-prolonging agents is not recommended, and abnormal electrolyte levels must be avoided.37,38 Importantly, kalaemia must be maintained in a high to normal range. Other antiviral strategies (e.g. specific neutralising antibodies) are under investigation. Detailed lists of interactions of antiviral and commonly used drugs are available at https://www.covid19-druginteractions.org from the University of Liverpool; at https://www.crediblemeds.org; and also in Driggin et al.16

Importantly, single-lead ECG with handheld devices will underestimate the QTc interval. Thus, for QT measurement, it is recommended to record 12-lead ECG, multi-lead handheld ECG, or single-lead handheld ECG in at least three lead positions.39 Both the absolute and delta QTc (incremental QTc) is required to establish the baseline risk and proarrhythmia.39 It is important to balance the risk of QTc measurement inaccuracy versus the risk of 12-lead ECG measurements in the pandemic situation. Maybe only high-risk patients should undergo systematic 12-lead ECG. Previous authors have been developing scores to predict the risk of QT prolongation with drugs. Although they are not validated for COVID-19, they are a clinical option.40

Advanced stages of COVID-19 are related to cytokine storm syndromes with elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g. IL-6 and high-sensitivity CRP), identifying patients at high risk of progressing to severe disease and even death.12,41 Therefore, corticosteroids and IL-6 inhibitors have been used for patients with refractory shock or advanced ARDS in small cohorts.42 Very limited data suggesting that adjunctive azithromycin to hydroxychloroquine might be useful has been published.18 However, this drug might prolong the QT interval and special caution should be paid if combined with hydroxychloroquine. Several other anti-inflammatory therapies are being investigated and might change the scenario in the future. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are obviously meaningful but unavailable yet, although promising results begin to be published.43,44

Conclusion

Because of limited testing and a large asymptomatic population, the true burden of SARS-CoV-2-infected people is still unknown and underestimated. Differing prevalences and clinical results might be (at least partially) explained by major differences in testing capacities between countries and regions, and by differences in test quality (sensitivity and specificity) but also by differences between populations. Diverse (direct and indirect) mechanisms may facilitate cardiac involvement resulting in myocarditis, ACS and diverse cardiac arrhythmias. Several antiviral strategies are under investigation. It can be hypothesised that (as for HIV treatment) a combination of drugs will probably achieve the best clinical results. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are urgently needed. Anti-arrhythmic treatments for COVID-19 are similar or identical to that for non-infected individuals. However, the avoidance of QT prolongation is essential, and possible drug–drug interactions must be considered. Elective procedures should be delayed, whereas urgent situations might require immediate treatment by trained and sufficiently equipped teams to ensure that healthcare workers do not become hosts or vectors of virus transmission.