During the 1980s and early 1990s, if you wanted to know more about my career – or the careers of my older brother, Pedro, and my younger brother, Ramon – all you had to do was ask our father. In fact, you probably didn’t need to ask. He kept dozens of scrapbooks, each overflowing with every titbit of news published by or about any of the three of us. And he made it a point to regularly regale friends and acquaintances with tales of his three cardiologist sons who – in his estimation – were clearly the most amazing sons any father had ever had.

You could hardly blame him. He was a brilliant man himself, but he never had the opportunities we had – opportunities he and my mother helped create for us. He supported our family by raising and selling rabbits and chickens, keenly aware, as he liked to explain, that the difference between profit and loss could be as narrow as the margin of a penny or two per animal. He worked a back-breaking schedule, rising at 4 or 4.30 am every morning and often working 14 or 15 hours a day before returning home as late as 10.00 pm at night.

But both he – and especially my prescient mother – were determined that my brothers, my sister Dolors, and I, would grow to have better lives. It was my mother who insisted that we stay in school and ultimately attend the University of Barcelona, 120 km south of Banyoles, Spain, the small Catalan village where we were raised. It was an expensive proposition, but my parents’ hard work and unyielding determination made it happen (Figure 1). Our mother even insisted that we learn to speak English, because, she said, it was the language of the future.

Thankfully, both of our parents lived long enough to see their dedication come to fruition and their improbable dreams come true. Three sons, three cardiologists – something no one could have predicted. Until then, there had never been a single physician in our family.

The final triumph for my father came just weeks before he died at the age of 74 years. Pedro, Ramon and I published the first book on Brugada syndrome. Seeing his name on the cover thrilled him and bolstered his conviction that he had helped raise the most remarkable sons on the planet.

A Role Model

How my brothers and I ended up where we did remains a bit of a mystery. We weren’t especially close growing up, largely because we were spaced so far apart. Pedro is 6 years older than I, and Ramon is 8 years younger. I was much closer to Dolors, who was just 2 years older than I.

However, Pedro was a role model who, according to our mother, showed an interest in medicine at a very young age – an interest I don’t remember myself having as a child.

Still, I was an impressionable 10-year-old when Pedro began studying medicine. It seemed remarkable, and as time went on I too became increasingly interested in the medical world.

These days, it’s impossible to start medical careers at such a young age, but Pedro was only 16 years when he began his medical studies, and I followed in his footsteps. As he had before me, I became a physician at the age of 22 years. At the age of 23 years, I married Anna, now my wife of almost 40 years, and at that remarkably young age the roadmap of our future lives seemed to be unfolding before us (Figure 2). By 25 years, I was a husband and a father – our daughter, Helena, was born 2 years after we were married – and the only physician in Riudarenes, a tiny village north of Barcelona where I worked as a general practitioner.

But by the time I was 25 years old, I was also becoming restless, thirsting for something that would provide more action than being a general practitioner in a small village. It was then that fate intervened, as it so often does, and a chance event dramatically transformed my life and my future.

Two close friends from medical school – a young man and young woman who had since married – came to visit Anna and me one weekend. At the time they were studying cardiology at the University of Montpellier in France, and seemed to be having the time of their lives. Why didn’t we join them there, they urged, but we would need to act fast, because the application deadline for the new year was just a couple of weeks away.

A whirlwind of excitement followed. I took a couple of days off, went with my friends back to Montpellier and stayed with them while I brushed up on my French – I spoke it at the time, but not fluently – and prepared for the entrance exam.

It was 1983, and when I passed the test, Anna and Helena soon joined me for a 4-year adventure that would change everything. It seems remarkable but true, in retrospect, that if my friends from medical school had decided to visit us in Spain 1 month later, I probably never would have been a cardiologist.

One More Obstacle

However, when those 4 years came to an end I wasn’t yet a cardiologist, and there were no guarantees. In fact, I had no idea how many of my classmates would fail to make it over the final hurdle – the national cardiology specialty exam in Paris, an extremely challenging written test. How challenging? Of the 240 who took it that year, only eight of us passed.

I knew I was well prepared, and I was confident, but I admit that the low success rate was shocking to me. I had figured maybe 20% or 30% would pass, not 3%. Fortunately, one of the major issues covered in the exam involved physiology research I was doing at the time. I had been working with animal models in Dr Antoine Sassine’s laboratory, studying different cardiac arrhythmias and the effects of different drugs on the electrical properties of the heart.

Although my brother Pedro was working with the Dutch cardiologist Hein Wellens and was already well known in the field of cardiac arrhythmia, he was in The Netherlands at the time, and in the pre-internet days, it was a lot more difficult – and a lot more expensive – to communicate internationally. As such, the help he could provide, though welcome, was limited. Pedro’s reputation helped me connect with my first important mentor, Professor Paul Puech, the legendary and marvellous French cardiologist who died last year at the age of 92 years old. Professor Puech helped facilitate the work I was doing in clinical cardiology, which also gave me a leg up.

Going Dutch

Shortly after the exhilaration I experienced when I was notified that I had passed, Anna and I had another momentous decision to make. I’d planned to return to clinical practice in Spain, but I’d also received an intriguing offer to combine clinical work and research at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in The Netherlands with Maurits Allessie, Hein Wellens and Pedro. The chance to do both, and to reunite with Pedro, was too tempting to refuse. So, in 1987, we set off on our next great adventure and eventually spent the next 4 years immersing ourselves in another new culture.

The Netherlands didn’t disappoint. The environment was warm and welcoming, and the entire experience was fantastic. By this time, we also had a son, Pau, and our children learned to speak Dutch and easily adapted to the Dutch lifestyle. They were happy and rewarding years, but the feeling of wanting to return home is stronger than any other feeling.

Fate stepped in again during one extraordinary week in 1991. An offer to work at the Montreal Heart Institute was followed days later by an offer from Professor Paco Navarro to return to the University of Barcelona, where I’d initially trained as a student, to initiate an arrhythmia unit.

When Anna heard of the offer, she reminded me about a conversation we’d had 8 years earlier, before leaving Spain for France. Why, she’d asked at the time, would I consider leaving? Because, I’d said then, someday I wanted to return to Barcelona and work as a cardiologist. The very opportunity of which I’d spoken had arrived, she reminded me. So we agreed: it was time to go home.

Home Again

To have a successful career at the University Hospital Clínic de Barcelona – probably the most important hospital in Spain in terms of scientific production – you not only have to be a good doctor, you also have to be able to do research. Fortunately, I brought extensive research experience with me from all my years in France and The Netherlands.

Having had the chance to work with Paul Puech, Antoine Sassine, Hein Wellens, Maurits Allessie and Pedro, I was at the forefront of the revolution taking place in the field of arrhythmias in cardiology. Until the 1980s and 1990s, we had spent a lot of time studying arrhythmias, but we didn’t have the tools to cure people. That changed with the introduction of catheter ablation. It was exciting. Patients who had suffered many episodes of tachycardia, who had been admitted to emergency rooms in some cases dozens of times, were simply cured, using ablation techniques. That changed not only their lives, but also our clinical practice.

But when I arrived back in Barcelona, there was no arrhythmia unit – I had to develop it from scratch. It was only a one-person unit at first, but within a year, our success rate and our patient volume began to soar and we started hiring more physicians to work in my unit.

After starting from zero, I became involved with everything in the hospital. Over time, I became a Professor of Medicine at the university, was named Chief of the Arrhythmia Unit, then Chief of the Cardiology Department, Director of what we call the Thorax Institute, and finally, in 2009, Chief Medical Officer of the hospital.

In 2015, I stepped away from my administrative positions, went back to clinical practice, and then came back as a senior consultant in cardiology. I’m still in clinical practice (Figure 3).

Family Tradition

Though I’ve led an enviable life, I’ve also experienced great sadness tinged with irony. Our beloved sister, Dolors, was stricken by sudden cardiac death at the age of 50 years old – at a time when her brothers were doing research in the field. It was nearly as unexpected as it was heart-breaking. She was very fit, and we had no family history of sudden death.

But the family tradition lives on in Dolors’ talented and extremely bright daughter, Georgia, who works as a cardiology interventionist in our paediatric ward (Figure 4).

I am the chief of the paediatric arrhythmia unit in our paediatric hospital, and I believe I was the first person in Spain to do arrhythmia procedures in children. I still work there 2 days per week, with Georgia, and I still do a lot of procedures in children from all over Spain. In fact, our unit is the only recognised reference unit in the country, which is something I’m very proud of.

One of my cardiac arrhythmia patients weighed about 1.5 kg, or less than 4 pounds. At the time of the surgery, he was the smallest arrhythmia patient ever. Now that young man is about 15 years old and doing very well. Now, he no longer holds the record. Last January, Georgia and I operated on a premature 30-week newborn with incessant tachycardia. She weighed 1.3 kg at the time and was in very poor condition. She has recovered completely, her heart is beating very well, and she’s beautiful.

Needless to say, procedures like these require very special expertise. They remind you that your career and all the hard work you’ve done is worth it.

Giving Back

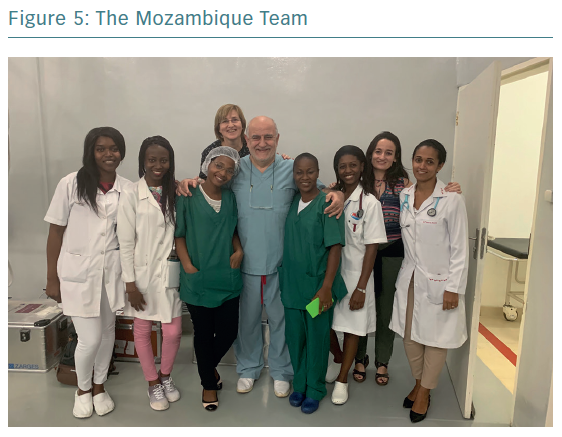

In recent years I’ve also made it a priority to give back what society has given me. For example, I use part of my time off and my holidays to go to Africa three- or four-times a year, and have been doing so for the last 7 years.

There, I work with children, because technology that’s useful and valid in children in Barcelona and New York should also be accessible to children in Mozambique and other extremely poor countries. I try to keep in mind Mother Teresa’s credo that if you cannot feed everyone, just feed one. I cannot cure everybody or solve all the world’s problems, but I can treat patients one by one, and I’ve now done more than 700 interventions in Africa (Figure 5).

I’m also doing what I can elsewhere. I’ve trained more than 200 people in electrophysiology from all over the world, and about half are from South America. In fact, I would estimate that about 60% of all the arrhythmia units in South America are directed by people who I have trained. I’m delighted that whenever I travel to South America, it seems as if there’s always an ex fellow of mine who wants to pick me up at the airport. I am also very proud that the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society, which is very well respected throughout the world, was largely created by former fellows of mine. These include Luis Aguinaga, Roberto Keegan, Luis Carlos Saenz, Marcio Figueiredo, Carlos Kalil and Ulises Rojel, to name a few.

I have had much recognition around the world and have been awarded many prizes, but these are minor compared to the joy I get from teaching, researching and doing clinical work.

Of course, from a scientific standpoint, the discovery of a rare cardiac arrhythmia that commonly causes sudden death and that’s brought about by a genetic defect is what I am most proud of. Brugada syndrome has led to respect and recognition all over the world, and the fact that initially Pedro and I discovered it together, then Ramon characterised the genetic aspect of the disease, is a source of great family pride. It will stay in the medical books forever, which means that our name and the name of our father will stay in the books forever (Figure 6).

No Plans to Stop

For now, I’ve just turned 61 years old and I have no plans to stop doing what I’m doing. Helping people is just so rewarding. I suppose someday, they may retire me and say: “You’re no longer able to do all these things, so please go home”.

Or maybe one day my wife will say it’s time to stop, and go to the beach and just enjoy our granddaughters, Júlia and Erin, and the many other grandchildren I hope will come in the future. For as long as I can, I’ll continue to do all the things I’m doing, because I’m so happy doing them. It’s difficult for me to imagine when or why I’d stop.