Smoking is a strong risk factor for the development of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD). Quitting smoking is a cornerstone of improved cardiovascular health, reducing the risk of developing CVD and the risk of overall mortality.1 It is astonishing that 7–28% of patients with coronary heart disease still smoke, but around half of smokers are planning to quit.2,3 Because the habit is addictive, it is crucial for cardiologists to repeatedly encourage patients to quit smoking. In addition, evidence shows that passive smoking increases the risk of CVD and that a significant number of people with CVD are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke.4 Such exposure should be avoided in CVD patients.

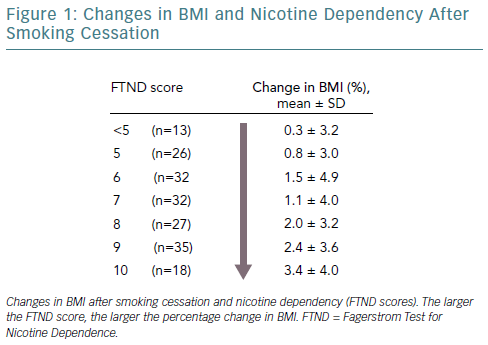

Smoking cessation is associated with weight gain.5 Individuals generally gain approximately 4–5 kg in the year after quitting smoking,and glucose and lipid metabolism also worsen.6 Weight gain often causes people to resume smoking. A study examined the factors associated with weight gain after quitting smoking based on data from the first visit to a smoking cessation clinic.8 Individuals with a higher score on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence displayed a greater change in percentage BMI after quitting smoking (Figure 1). These findings indicate that nicotine dependence and weight gain after quitting smoking are statistically related and strongly support the hypothesis that weight gain after stopping smoking is a symptom of nicotine withdrawal. If weight gain after quitting smoking can be predicted prior to smoking cessation interventions, then that weight gain might be prevented.

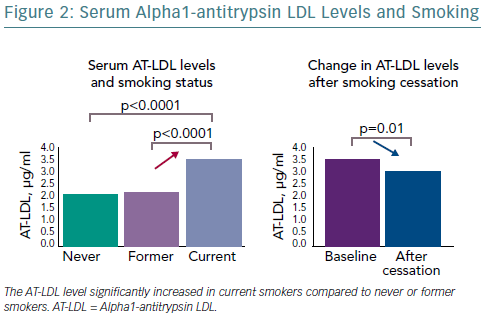

It is not known whether weight gain after quitting smoking exacerbates CVD. The alpha1-antitrypsin LDL (AT-LDL) complex, a complex of alpha1-antitrypsin (AT)-oxidised LDL, is an important cardiovascular biomarker. Smokers have considerably increased serum AT-LDL levels, compared with non-smokers, and AT-LDL levels have been shown to significantly decrease 3 months after quitting smoking (Figure 2).9 A study that examined the effects of weight gain after quitting smoking on AT-LDL levels found that AT-LDL levels decrease as a result of quitting smoking, but this improvement was not reported in obese individuals after quitting smoking.10 Essentially, weight gain 3 months after quitting smoking may hamper improvements in AT-LDL levels. However, 1 year after quitting smoking the serum AT-LDL levels decreased to a greater extent than the levels 3 months after quitting smoking, regardless of whether obesity increased.11 In other words, the benefits of quitting smoking outweigh the disadvantages of weight gain over time, and quitting smoking reduces the risk of developing CVD.

A large-scale 14-year cohort study examined the relationship between smoking cessation and stroke events among postmenopausal women.11 A significant reduction in stroke risk by smoking cessation was not attenuated by concurrent weight gain. Another large-scale follow-up study, conducted over 30 years, examined weight gain after quitting smoking and the subsequent risk of illness or death.12 According to this study, weight gain peaked 6 years after quitting smoking and 35% of the subjects gained 5 kg or more. If an individual gains 5 kg or more after quitting smoking, their risk of developing diabetes increases by 40–60% compared with individuals who continue to smoke. However, the increased risk peaks approximately 6 years after quitting smoking; 30 years after the individual quits smoking, they have the same risk of diabetes as that of a non-smoker. If an individual quits smoking, their risk of death as a result of CVD and any other cause significantly decreases, regardless of weight gain (even if they gain ≥10 kg). Nonetheless, individuals who do not gain weight display greater reduction in the risk of developing CVD than those who do gain weight. Clearly, weight management is crucial after quitting smoking. If an individual gains 20 kg 6 years after quitting smoking and does not lose that weight, their risk of cardiovascular death increases each year. Furthermore, individuals who have not lost that weight even 30 years after quitting smoking have the same risk of cardiovascular death as that of individuals who continue to smoke; hence, caution is required.

A large-scale cohort study analysed patients with diabetes and those without who quit or continued to smoke.3 Compared with current smokers, patients without diabetes were reported to have a considerably reduced risk of developing CVD over 4 years after quitting smoking. This finding held true even if the people without diabetes gained a substantial amount of weight. In addition, the risk of developing CVD decreased the longer the people without diabetes abstained from smoking. People with diabetes displayed a reduced risk of developing CVD if they abstained from smoking for at least 4 years and if they gained less than 5 kg. However, gaining an excessive amount of weight (>5 kg) annulled the reduction in risk of cardiovascular events caused by quitting smoking. Thus, people with diabetes should carefully monitor weight gain after quitting smoking.

A randomised controlled trial examined the timing of instruction in weight management when implementing a smoking cessation intervention.14 According to this trial, the rate of successfully quitting smoking decreased when instructions regarding quitting smoking and managing weight were simultaneously provided from the beginning of the intervention. Individuals must be informed of the advantages of quitting smoking and they need to abstain from smoking. Once the individual has consistently abstained from smoking, they must be provided with support to gradually decrease their weight. Exercise therapy and psychological support help limit weight gain after quitting smoking.

In conclusion, weight gain generally occurs after smoking cessation and this temporarily increases the risk of diabetes and reduces the benefits of smoking abstinence. The benefits of smoking cessation may be minimised by obesity in those who have stopped smoking. However, continued abstinence from smoking will, over time, outweigh this. CVD risks never increase by stopping smoking, even if excessive weight gain occurs. Based on these results, it is crucial that physicians and other medical professionals support patients to continue smoking cessation and to gradually decrease their weight.