Background

Definition of Stable Angina

Angina pectoris was first defined by William Heberden in 1768. He described it as a smothering sensation or tightness across the front of the chest which may radiate to the left arm or to both arms as well as the jaw or back. It is usually triggered by exercise or emotional stress and it may be aggravated by the ingestion of a heavy meal.1 The pain usually resolves by stopping exercise or with sublingual nitroglycerin. Angina is arbitrarily defined as stable when the angina episodes are stable over a period of 3–6 months.2,3 Atypical features, such as shortness of breath during exercise in the absence of pulmonary disease or extreme fatigue during exertion, have been considered as angina equivalents.4 These atypical presentations in the absence of chest pain are often found in women, older people and people with diabetes.

Causes of Stable Angina

The exact aetiology of stable angina is not well defined; however, it is thought to be secondary to a mismatch between myocardial supply and demand.5 The majority of patients with angina have significant narrowing of one or more epicardial coronary arteries. It is also recognised that many patients with stable angina have non-obstructive or even normal coronary arteries.

Prognosis for Patients with Stable Angina

The prognosis for patients with stable angina varies, but there is an annual mortality rate of up to 3.2%. Long-term prognosis is influenced by left ventricular systolic function, extent of coronary artery disease (CAD), exercise duration or effort tolerance, and comorbid conditions.3 The published data does not account for medical interventions, such as statins and aspirin, which reduce mortality and morbidity in coronary artery disease, and it is likely that the prognosis of stable angina without medical therapy may be very different.4

Pharmaceutical Therapy

Nitrates, Beta-blockers and Calcium Channel Blockers

Nitrates are available in different formulations and both short- and long-acting organic nitrates have been shown to be effective in treating angina when used appropriately to avoid nitrate tolerance.3,6,7 Nitrates are as effective as beta-blockers (BB) and calcium channel blockers (CCB).8 Sublingual nitroglycerin tablets and oral nitroglycerin spray are rapidly absorbed and when taken prophylactically can improve exercise tolerance and reduce the incidence of MI.9,10 One of the major side-effects of nitrate use is headaches that may be severe enough to necessitate discontinuation of the therapy.11 Tachyphylaxis, or tolerance to continuous use of nitrates is another limiting factor, but can be avoided by allowing prolonged nitrate-free intervals for nitrate levels to decline before the next dose.6,7,9,12 Long-acting nitrates have been downgraded to second-line therapy in guidelines because of their side-effects and the incidence of tachyphylaxis.

The first reported use of BBs to treat hypertension and angina was in the 1970s in the UK.13,14 BBs are an effective therapy in the management of stable angina.14–17 Many BB are available for clinical use. They have the common property of blocking beta-adrenergic receptors and selective and non-selective BB can be chosen for their different properties. Although BB can reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and in patients with recent MI, these agents have a limited effect on mortality and the incidence of MI when used in patients with stable angina.18–26

CCBs, both dihydropyridine (DHP) agents and non-DHP agents, have been used for more than five decades, and are very effective for the treatment of stable angina. They significantly reduce the episodes of angina, increase exercise duration and decrease the frequency of nitroglycerin use.27–30 When combined with BB, they have been shown to significantly delay the onset of ST-segment depression using an exercise treadmill test.31 Patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are good candidates for treatment with CCB, given the risk of bronchospasm in these patients when taking BB.32 A combination of BB and non-DHP CCB should be avoided due to the risk of symptomatic bradycardia and atrioventricular block.33

Nicorandil, Ranolazine, Trimetazidine, Ivabradine and Allopurinol

Nicorandil, which is a nitrate-moiety nicotinamide ester and adenosine-sensitive potassium channel opener, increases coronary blood flow and prevents coronary artery spasm.34 It has been approved for clinical use in Japan and many European countries on the basis of small trials in patients with stable angina.35,36 This medication is not used in the US because placebo-controlled studies from Australia and the US failed to confirm antianginal efficacy of nicorandil compared with placebo.37 In Europe, it has been used instead of nitrates or in combination with other antianginals.37 Side-effects of gastrointestinal ulcerations and headache limit the long-term use of nicorandil in patients with stable angina.38,39

Ranolazine is an orally active piperazine derivative.40 The exact mechanism its antianginal action is unknown, but animal studies have shown that it inhibits late sodium inward current during periods of ischaemia, reducing intracellular calcium overload.41,42 Ranolazine is an effective antianginal and anti-ischaemic agent compared with placebo and is as equally effective as atenolol.43,44 Extended-release ranolazine compared with placebo, as monotherapy or in combination with other antianginals, has been shown to significantly increased total exercise time by 116 seconds and 23.7 seconds, respectively.43,44 It also increased treadmill walking time for people with angina and delayed the onset of exercise-induced MI.43,45,46 Ranolazine has been shown to be ineffective in the treatment of women with microvascular angina compared with placebo.47

Trimetazidine is available in Europe and several countries in Asia as an adjunct therapy for angina, but it is not used in the US.4,35,48 In patients who remain symptomatic despite treatment with first-line therapy drugs, trimetazidine decreases angina frequency without exerting any effects on heart rate or blood pressure, as shown in the TRIMetazidine in POLand (TRIMPOL) trials I and II.49,50

Allopurinol is a pyrazolopyrimidine and an analogue of hypoxanthine.51,52 It has been demonstrated that high-dose allopurinol is associated with a significant improvement in endothelium-dependent vasodilation and exercise tolerance. The effects of high-dose allopurinol (600 mg daily) have been shown to be similar to conventional antianginal medications.53 While recommended in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines as a second- or third-line agent for symptom control, allopurinol is not endorsed in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.35,54,55 Allopurinol is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat angina in the US.

Ivabradine lowers heart rate and inhibits the primary sinoatrial node current.56 It is use-dependent, meaning that its effect is the highest in high heart rate and vice versa; bradycardia is less commonly encountered in patients on ivabradine because its effect is ameliorated at lower heart rates.57 Studies have shown that ivabradine as an add-on therapy to atenolol significantly increased exercise time and reduces the number of angina attacks compared with atenolol alone or other BB and it did not cause significant bradycardia.58–61 However, symptomatic bradycardia remains a concern when using combination therapy, and it may adversely affect outcome in severely symptomatic patients.33 In patients with stable angina without heart failure, ivabradine added to background therapy was shown not to decrease the incidence of death from cardiovascular causes or non-fatal MI, but in a subgroup of patients with severe angina, ivabradine performed worse than placebo with regards to hard endpoints.62

Combination Antianginal Therapy

Monotherapy in optimal doses,is often as effective as combination therapy using two or more agents.3,4,35,63,64 There is a lack of well-designed studies showing that treatment with more than one class of drug is superior to combination treatment with a different class of antianginal drugs.65,66 Adding either a long-acting nitrate or a CCB to BB therapy is often useful and reduces angina frequency, improves exercise tolerance and reduces MI.63,65 A combination of BB and ivabradine has been shown to be effective in patients with a heart rate greater than 60 BPM, but safety concerns have been raised.62,67 As discussed earlier, extended release ranolazine monotherapy, or in combination with BB or CCB, is effective.43,45,46 Trimetazidine as an add-on to older antianginal drugs has also been shown to be effective.44,45

None of the trials involving a combination of antianginal drugs have been adequately blinded to make firm conclusions regarding the superiority of a combination of two antianginal drugs to doses of monotherapy. Data on the efficacy of triple therapy with three different classes of antianginal drugs are not available.

Guidelines for Stable Angina

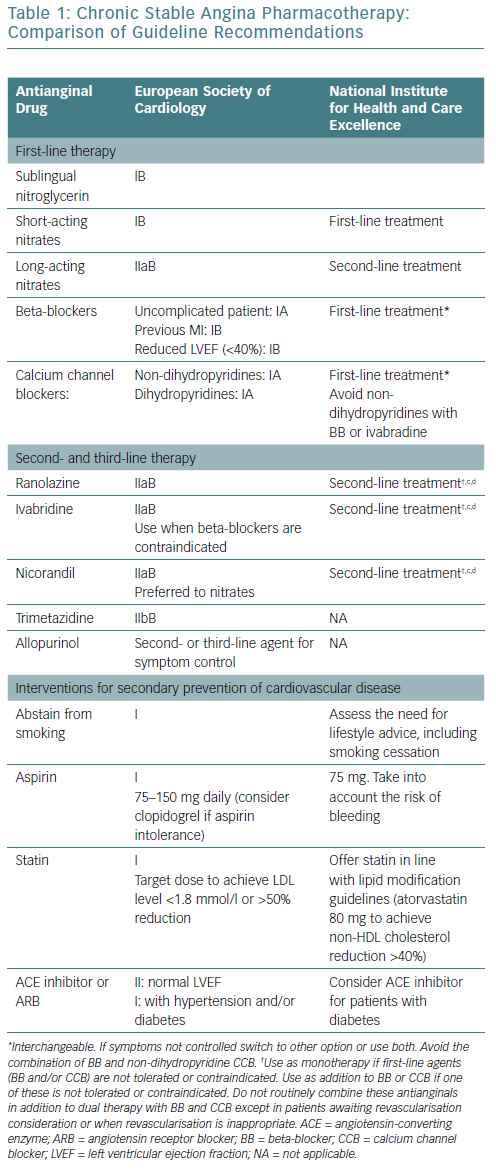

There are published guidelines for the management of patients with stable ischaemic heart disease and stable angina. The ESC and NICE guidelines have been updated regularly to provide a clear set of guidelines for management for healthcare professionals in the UK and Europe.35,54,55 ESC guidelines (Table 1) provide recommendations divided into classes:

- Class I where the evidence and/or general agreement that a given treatment or procedure is beneficial, useful and effective.

- Class IIa where the weight of evidence or opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy.

- Class IIb where usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence or opinion.

- Class III where there is evidence or general agreement that the given treatment or procedure is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful.35

In addition, for each class of recommendation, a level of evidence is included:

- Level of evidence A denotes that data were derived from multiple randomised clinical trials or meta-analyses.

- Level of evidence B indicates that data were derived from a single randomised clinical trial or large non-randomised studies.

- Level of evidence C is where a consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, retrospective studies or registries were available.35

NICE guidelines (Table 1) are based on extensive reviews of published data and take into consideration cost-effectiveness and the adverse effects of medications. The terms first-line treatment and second-line treatment are used and guidance is given on the most appropriate use of antianginal therapy, taking co-morbidities into consideration when selecting therapy.54,55

Guidelines for Antianginal Therapy

A previously published article compared the American and Canadian guidelines.65 This article compares the recommendations for antianginal therapy in ESC and NICE guidelines (Table 1). Both sets of guidelines agree that optimal medical therapy includes antianginal therapy and medications to prevent MI and stroke, including aspirin and statins. They both favour the use of sublingual short-acting nitrates for the relief of an established attack of angina or for prophylaxis. Both guidelines recommend the use of BB or CCB as first-line therapy with the notion that non-DHP CCB should not be combined with ivabradine or BB.

NICE guidelines recommend a trial of a maximally tolerated dose of either a BB or a CCB as initial therapy. If there are contraindications to one class of drugs or no response, switching to a CCB from a BB and vice versa should be considered. If the response to one class of these antianginal drugs is sub-optimal, NICE recommends a combination of a BB with a DHP-CCB as preferred combination therapy. Use of second-line drugs (long-acting nitrates, nicorandil, ranolazine or ivabradine) as monotherapy or in combination therapy is only recommended when there are contraindications to first-line drugs. Triple therapy is only recommended when patients are being considered for possible revascularisation and remain symptomatic despite treatment with first-line agents. ESC guidelines are more liberal on the use of combination therapy with two or more agents.

ESC guidelines specify certain subsets of patients who would benefit from BB (patients with previous MI and patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction), while NICE guidelines do not have any specific patient subgroups. Ranolazine, ivabradine, and nicorandil are considered to be second-line treatments based on both guideline documents. While trimetazidine and allopurinol are recommended as second- or third- line therapy in the ESC guidelines, NICE guidelines do not endorse the use of those medications for patients with stable angina.

Co-morbidities and Stable Angina

Both guidelines recommend use of specific antianginal medications, taking into consideration the presence or absence of comorbidities such as COPD, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease and diabetes, despite the lack of randomised controlled trials to support this.64,65,68

Guidelines to Reduce MI and Sudden Cardiac Death

Lifestyle Changes

Smoking cessation or abstinence reduces the risk of CAD mortality by 50% in 1 year and after 5–15 years the coronary mortality risk reaches that of non-smokers.69 In addition to decreasing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, stopping smoking in patients with angina also increases exercise performance.64 Although based on small observational studies, exercise training was shown to have favourable outcomes in patients with stable angina.70 Both guidelines emphasise the importance of smoking cessation and regular exercise. NICE guidelines do not specify any special diets, while ESC guidelines recommend a Mediterranean diet. Cardiac rehabilitation is recommended in ESC guidelines, but not in NICE guidelines.

Antiplatelet Therapy

Both guidelines recommend daily use of low-dose aspirin because it has been shown to reduce the incidence of acute MI and sudden death in patients with known CAD.71 This has only been shown to be effective for patients with stable angina in a small study.72 The use of aspirin in patients with stable angina in the absence of CAD is uncertain.65 In patients who are allergic to aspirin, clopidogrel may be used instead according to ESC guidelines, but is not evidence-based; although routine combination of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is not recommended due to an excessive risk of bleeding.73

Treatment of Dyslipidaemia

There are no specific trials of statins in patients with stable angina, however this class of drugs reduce all-cause mortality, acute coronary events, and the need for revascularisation in patients with CAD and in those at high risk of CAD.74,75 ESC guidelines recommend the use of statins to achieve the ideal low-density lipoprotein goal (<1.8 mmol/l), while NICE guidelines recommend the use of high-dose statins, such as 80 mg atorvastatin (Table 1).

Control of Hypertension

There are no specific trials of antihypertensive medications in patients with stable angina who also have hypertension. But given the documented beneficial effects of controlling blood pressure on hard outcomes, especially stroke and heart failure, both guidelines recommend optimal control of blood pressure in patients with stable angina to reduce the incidence of stroke and MI. The blood pressure goal is <140 mmHg for systolic, however recent data suggest that lowering systolic blood pressure to 120 mmHg may be a desirable option if tolerated by the patient.76,77

Management of Diabetes

Diabetes is commonly found in patients with stable angina. Control of diabetes reduces micro- as well as macrovascular complications. Based on the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes (ACCORD) trial, an HbA1C level <7% is desirable.78 Both guidelines recommend routine use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) for patients with stable angina who have diabetes.

Concomitant Management of Patients with Angina and Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

There are no randomised controlled trials that have studied patients with stable angina and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Based on the available outcome trials showing survival benefit, the use of BB and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or ARB is recommended in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction <40% and concomitant angina.4,19,79–82

Treatment of Patients with Stable Angina and Normal Coronary Arteries or Microvascular Angina

NICE does not make any specific pharmacotherapy recommendations for patients with stable angina and normal coronary arteries or microvascular angina, while ESC guidelines recommend a trial of antianginal drugs. There are no efficacy trials regarding hard outcomes in patients with stable angina who have normal coronary arteries.65 Current evidence does not support the routine use of aspirin or statins in patients with microvascular angina who have normal coronary arteries.

Identification of High-Risk Patients with Left main or Severe Triple Vessel Coronary Artery Disease

Updated NICE guidelines recommend use of coronary CT angiography for an initial investigation for all patients with typical and atypical angina to define coronary anatomy non-invasively, even if the patients are adequately treated with pharmacotherapy.83 This is based on available data showing that coronary artery bypass surgery is superior to medical treatment in this group of patients. ESC guidelines, on the other hand, use non-invasive stress testing to define a high-risk group.83

Conclusion

The current guidelines are largely based on expert opinion and consensus rather than high-quality randomised controlled trials. The two documents discussed in this article make different recommendations for first-line treatment, as well as add-on treatment with two or three antianginal drugs, without objective data.

Secondary prevention strategies vary; however, the use of low-dose aspirin and statin therapy seem to be justified based on the available data. The management of patients with microvascular disease or normal coronary arteries and angina remains uncertain especially in the absence of randomised controlled trials. The guideline recommendations rely mostly on assumptions and extrapolations and expert opinion based on the available data regarding patients with obstructive CAD.